Recent Posts

- Venice 2023July 25, 2023

- Paris 2019October 18, 2019

- Moffly Media’s athome magazine A-List Awards 2019September 13, 2019

- Venice 2023

Archives

Categories

Eyford Park was a revelation (helped, not a little bit, by a warm spring afternoon, the pale local stone glowing in the sun’s low angle); a simple, symmetrical composition, reimagined thousands of times in colonial materials, but as you walked up to it, the power of its subtlety gets borne-in: nothing quirky or unusual—all well-known classical elements—but layered-on sparingly, the proportion and scale so elegant…

Eyford Park was a revelation (helped, not a little bit, by a warm spring afternoon, the pale local stone glowing in the sun’s low angle); a simple, symmetrical composition, reimagined thousands of times in colonial materials, but as you walked up to it, the power of its subtlety gets borne-in: nothing quirky or unusual—all well-known classical elements—but layered-on sparingly, the proportion and scale so elegant…

And the mews—the car-court—much more offhand—no Palladian allusions here—but beautifully balanced nonetheless…

And the mews—the car-court—much more offhand—no Palladian allusions here—but beautifully balanced nonetheless…

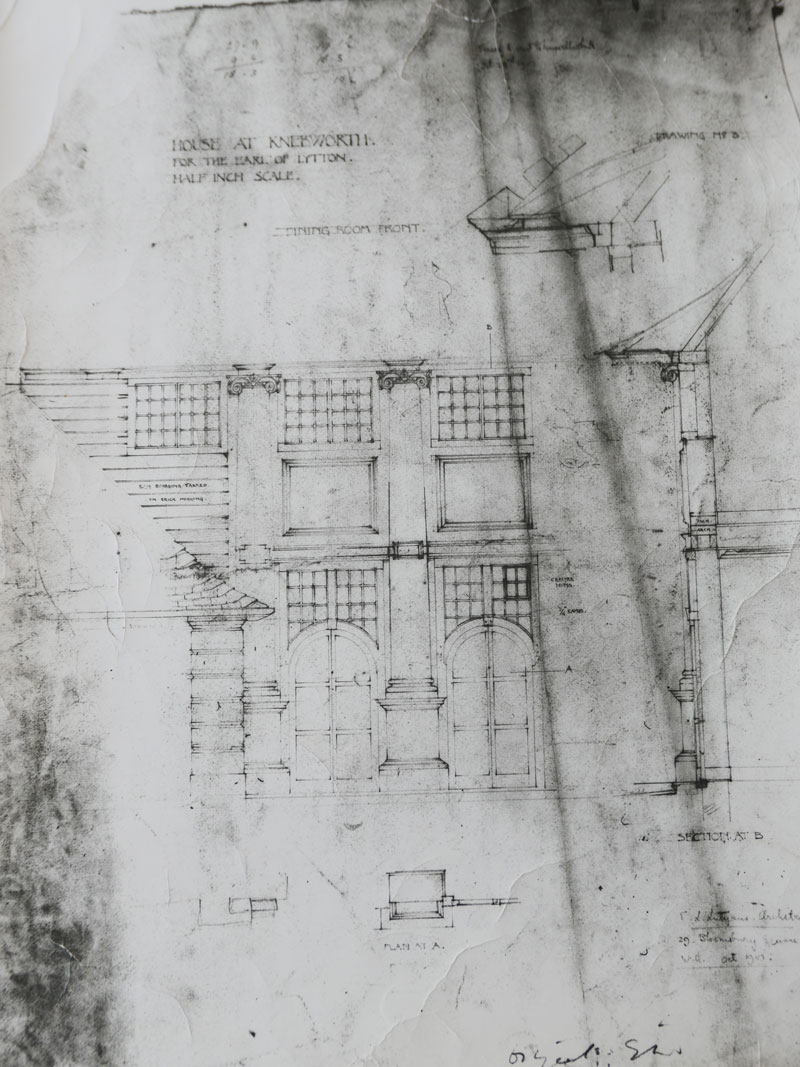

Homewood, at Knebworth, was a house I thought I knew well from photographs, but seeing it in the flesh surprised me; so small, compared to your typical English country seat, and—until you walk around back—a rustic vernacular cottage, sided in bare elm clapboards…but, on the garden side a painted classical façade busts-out through the roof:

Homewood, at Knebworth, was a house I thought I knew well from photographs, but seeing it in the flesh surprised me; so small, compared to your typical English country seat, and—until you walk around back—a rustic vernacular cottage, sided in bare elm clapboards…but, on the garden side a painted classical façade busts-out through the roof:

Perhaps the best example I’ve seen (yet) of how inventive and inspired traditional architecture can be. And wonderfully playful with scale; the chair in the detail shot shows the scale;

Perhaps the best example I’ve seen (yet) of how inventive and inspired traditional architecture can be. And wonderfully playful with scale; the chair in the detail shot shows the scale;

Those arc-topped French doors are less than head-height; the room behind is a (small) dining-room—you look out form a seated perspective—and doors in and out of the drawing-room next door are via the loggia, where your hair brushes the soffit as you walk under…all very deliberate, but just as drawn.

Those arc-topped French doors are less than head-height; the room behind is a (small) dining-room—you look out form a seated perspective—and doors in and out of the drawing-room next door are via the loggia, where your hair brushes the soffit as you walk under…all very deliberate, but just as drawn.

At another country house—this one a big renovation—the severe Georgian garden façade is enlivened by a delightful mannerist flourish:

At another country house—this one a big renovation—the severe Georgian garden façade is enlivened by a delightful mannerist flourish:

The door’s architrave is “eroded” from flush, plain stone of pilasters, quoins and casing:

The door’s architrave is “eroded” from flush, plain stone of pilasters, quoins and casing:

The simple, beautiful molding of cove, pulvinated frieze and broken pediment are offset by the plain exclamation point of the keystone…note too the main floor’s double-hung sash; they look “normal” in the photo, but they’re huge—more than 7 feet tall by themselves—standing below 12-foot ceilings above…

The simple, beautiful molding of cove, pulvinated frieze and broken pediment are offset by the plain exclamation point of the keystone…note too the main floor’s double-hung sash; they look “normal” in the photo, but they’re huge—more than 7 feet tall by themselves—standing below 12-foot ceilings above…

Even when Luytens worked on market-spec or “estate” housing, the invention in detail is so delightful; at first you notice lovely—if straight-forward detail;

Even when Luytens worked on market-spec or “estate” housing, the invention in detail is so delightful; at first you notice lovely—if straight-forward detail;

But then you see a stair-hall’s window break through the eave:

But then you see a stair-hall’s window break through the eave:

Or a door-frame lifted twelve feet high over a transom, to light another stair-well:

Or a door-frame lifted twelve feet high over a transom, to light another stair-well:

Or a rusticated archway, complete with beaux-artes triglyphs, leading you back to service court beyond (clearly just there as a whimsical delineation between two units, left and right)…

Finally, a typical English country-house table-scape; museum-worthy little sculpture tossed on a window-sill, with some twine trying to hold the steel sash closed…

Or a rusticated archway, complete with beaux-artes triglyphs, leading you back to service court beyond (clearly just there as a whimsical delineation between two units, left and right)…

Finally, a typical English country-house table-scape; museum-worthy little sculpture tossed on a window-sill, with some twine trying to hold the steel sash closed…

Skylight photo at top, and window bay at bottom both from Ashby St. Ledgers…

Skylight photo at top, and window bay at bottom both from Ashby St. Ledgers…